Chanel Enforces Legal Rights over Its N°5 Perfume Trademark

So prominent is the number five in realm of luxury fashion that most of us associate it as the namesake of one of the world's most famous perfumes - Chanel No. 5, the first fragrance launched by Gabrielle 'Coco' Chanel in 1921 and later trademarked by the company in 1926.

According to reports, the Paris-based design house, is now taking legal action against a small South Australian chocolate company that has been forced to change its business logo after being issued with a cease-and-desist letter from Chanel lawyers, last month - citing trademark infringement of the No. 5 branding.

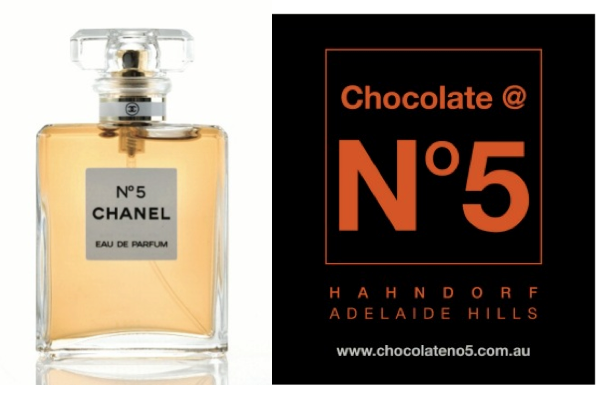

The issue ignited when 'Chocolate @ No. 5', a small chocolatier in South Australia, tried to register a trademark for its logo. Alison Peck, the owner of 'Chocolate @ No. 5', filed to register her shop's logo as a trademark with the Australian Intellectual Property Office. The logo bore a distinct likeness to the perfume's label in its visual representation of the number five. Chanel's legal team later filed an action to oppose Peck's mark and demanded that she withdraw her registration, change her logo and refrain from using the digit or word "five" in her business name.

Note the similarity between the Chanel No. 5 logo, left, and the chocolate maker's original logo opposed by Chanel, right.

Peck complied with the first two demands, but insists that she named her store after the shop's address, 5 Main Street: "I was not trying to pass off my chocolates as being Chanel No. 5. That's just silly because it's chocolate."

While this may never have been her intention, this case highlights some important IP issues. International luxury brands like Chanel are at a distinct advantage over smaller, less well-known brands when it comes to the protection of their trademarks. The high level of recognition that a "famous" mark such as Chanel No. 5 enjoys in the global marketplace translates into a high level of protection under trademark law.

So even if goods or services have little connection or do not compete with one another - even if they are as different as Chanel and chocolate - the concept of trademark dilution comes into play to preserve "aura of luxury' associated with the original trademark.

Seen through this lens, it becomes clear that although not identical, 'Chocolate @ No. 5' 's logo is one that at the very least creates an association with Chanel No. 5. Arguably, the graphic representation of the number five and the font is probably enough to create 'confusion' in the mind of a not-so-savvy clientele, this is because according to the concept of trademark dilution due to the reputation of well-known mark, any use by another of that mark creates a likelihood for confusion, since a famous mark is so well known among the public that people will associate it with the owner of that mark even where the products or service being marketed under the name are different. use.

famous marks, any use by another person of the mark has the potential for confusion, since a famous mark is so well known among the consuming public that people will assume affiliation with the owner of the mark regardless of the product or service being sold under the infringing use.

According to a Chanel spokesperson, however, there was actually a little more to the story:

"Chanel's main concern was that Ms Peck was also using and had applied to register as a trade mark the No. 5 label in a strikingly similar black and white font for perfumed candles. Chanel only asked Ms Peck to withdraw the label applications and that over time she reduce the font size of No. 5 on her labelling."

In the world of trademark, it is the sole responsibility of trademark owners to safeguard their own marks from unauthorised use. Companies with international business depend on a solid understanding of the scope of their marks' protection in different markets to ensure protection and enforcement - and this is exactly what Chanel was doing here.

Along with the interlocked Cs, No. 5 is perhaps Chanel's most valuable trademark, not to mention the widely documented mythical significance the number represents for the maison. Being her lucky number, it seems almost pre-destined that the fragrance, which would become one of the signatures of her fashion house, was the fifth vial presented to Mademoiselle Chanel by her Master Perfumer: "I present my dress collections on the fifth of May, the fifth month of the year, and so we will let this sample number give keep the name it has already, it will bring good luck," she stated.

As Chanel's good fortune persists almost a century later, things are not so sweet for Peck. After spending "a few thousand dollars" on her trademark registration, she withdraw her application and chose to rebrand her logo completely, claiming she felt "bullied".

Chanel, however, stated that they were simply asserting their IP rights and that they were seeking a mutually acceptable solution that did not necessarily involve a full rebranding of Ms Peck's business: "Chanel is always mindful of the need to balance the protection of its trade mark rights with the rights of others to trade freely. That is why Chanel did not object to Ms Peck's application to register the word mark: 'Chocolate @ No. 5' for chocolate drinks and various chocolate food products - biscuits, confectionary etc."

Caveat emptor to FLB readers. Until further notice, No. 5 reigns supreme. Help yourself to some chocolate, but don't mess with Chanel

SARAH AUSTIN is a Contributing Editor and Writer at Fashion, Law & Business. Sarah is an Australian Qualified Lawyer based in London, having completed a Bachelor of Arts and a Bachelor of Laws at the University of Sydney. She has a special interest in the intersection between fashion, luxury, art and the law, which blossomed from her final year research paper, 'Copyright à la mode: Comparative insights into fashion design protection in France and the United States'. Sarah recently completed a course in Art Law at Sotheby's Institute of Art and is currently working as a freelance lawyer at a magic circle firm in London.